Cyber Knights: Flashpoint review | Rock Paper Shotgun

Cyber Knights: Flashpoint has some excellent nonsense scenario writing propping up mission design. In one early excursion, you remote activate ‘defector tech’ to convert an enemy agent over to your side, then have a turn to neutralise the neuro-toxin killswitch in their brain with injectors. The game is awash with this sort of campy, techy gangslang. My absolute favourite of these so far is ‘chumbo’ – apparently a much stupider, funnier, and therefore much better version of 2077’s ‘choomba’.

Similarly, Cyber Knights’ script is pure cyberpunk American cheese singles; reliably tropey and enjoyably naff. And yet, I have spent the last week or so popcorn-bucket-deep in the game’s drama. There’s little as gripping as a good heist; the planning and personalities and stakes, the fated fumbles and slick improvisations. And, once it gets going, CK:F’s grip is augmented. Hour one: “lol, chumbo”. Hour three: “We’ve been made, chumbos! Go loud!”.

Part ganger management sim, part cyberpunk underworld-navigating RPG, and part stealth-tactics heist ’em up, the thing Cyber Knights is best at is making me personally feel very cool. I went to rinse off a spoon yesterday but apparently forgot that spoons are curved and spray water in a powerful arc if you hold them under a tap. I do not need a power fantasy. A hyper-competency fantasy suits me just fine.

That said, its sheer breadth of linked and fleshed-out ideas can feel surveillance-state oppressive at first, as if hidden cameras are watching for signs of discomfort or confusion on your face so the corpogov can file you in their database of big dumb chumps. You’ll often find strategy games with an easy hook obscuring hidden crunch, but this is sort of the opposite – proudly flashing its bitty and tangled grognard bonafides before revealing itself to be quite a smooth, intuitive ride, just one that revisited the cutting room floor after hours and shoved every idea it could find into its massive techwear pockets. It’s in making all those ideas relevant contributors to its tactical theatre that CK:F really shines.

No Ship of Theseus references so far either, thank Gibson. CK:F’s answer is implicit, anyway: remove the parts, the whole just isn’t the same, so let’s cover a scav mission in action. In the final turn, my sword-wielding Knight J.C ‘Dental’ Floss will find herself pinned down by a shotgunner’s overwatch cone, before remembering she packed a syringe of evasion juice, slamming it, then dancing gracefully to the evac elevator. But we start out without a soul aware of our presence, calling in fixer favours and spending a few spare action points on abilities to disable cameras and laser sensors. We move between safes, lifting blueprints and valuable programs. We distract the guards we can with thrown lures. We take out the ones we can’t with silenced pistols and swords.

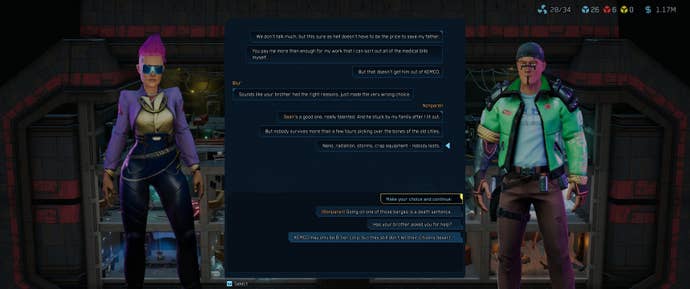

The management layer feeds into the RPG layer feeds into the tactics layer and loops back. We extract once we’ve loaded up on loot. Once we return to base, the loot goes in cold storage to be sold to fixers for cash or favours. If someone likes us a lot, they might set us up with missions or new recruits. We customise those recruit’s backstories through detailed (if long-winded) conversations, defining personal baggage like errant siblings or debts that surface later as optional missions. Helping a black market contact out might mean better gear is available to buy, or we can synthesise our own from the blueprints we stole once we build fabricators.

Or we might want to invest in counter-intel or medical facilities instead if we got sloppy on the last mission, got people wounded or stressed or brought down heat, resulting in negative traits and recovery time and headhunter mercs interrupting us on missions. And this sounds overwhelming but it all flows naturally. Before we know it, we’re back in the field.

CK:F works on an initiative system, with a turn gallery keeping you up to speed, but you can opt to delay a merc’s turn as many times as you want, knocking 10 initiative off each time until they’re reduced below that number. On the simpler end, this lets you do things like kick turns off with the specific ability you need, or keep your gunnier chumbos in reserve if things go the way of the pear, or just wait to see what the guards do first, providing you’re safely hidden and have preferably used some tracking tech to predict movement routes. On the more involved end, you can use it to pull guards apart and pick them off one by one, or set up lovely kill combos.

But this stuff really comes to life in how well it drives home that these turns you might be engineering for fifteen minutes apiece are really playing out in seconds for the characters. Your gangers might look like mismatched techno club casualties, but they can execute like disciplined surgi-bastards. This extends to the stealth. When you slip up, guards are alerted to your presence independently of each other, meaning you can react, eliminate suspicious threats, and slip back into the shadows. I once had Dental lope through grenade smoke and pick off stragglers with her sword. I’m not actually positive this did much but, again, it did make me feel very good at my pretend cyber job.

They won’t rush to set off any sort of map-wide alarm, either. Yellow pips on an alert tracker mark temporary danger, and it’s mightily satisfying to clear that bar by taking out problems before they turn blue as permanent ticks toward reinforcements at the end of a turn. But this can also make stealth feels a little fuzzy and esoteric. You’re always reliably informed whether you’ll be spotted or heard, either by guards or security devices, but I still haven’t quite nailed down what feels like some hidden variables toward alerts spreading to other guards on the map. I murder seven dudes. Trip a motion detector. Get seen by two cameras. Reinforcements show up, wander around for bit. “Glitches again. Must be monday”.

In fairness, this might have had something something to do with the hacking I’d just done. This is the second version of the hacking tutorial the Trese Brothers have added, and it still gave me an anxiety attack followed by a shorter, more intense anxiety attack followed by what I’m sure was permanent psychosomatic cranial damage. I eventually looked up an older tutorial on the Brothers’ YouTube channel which was much better. This should be in the game. It’s cyberpunk. Just do a Max Headroom thing with a vocoder, it’ll be fun.

Anyway, the very basic gist here is that you spend AP to move between nodes and use memory to load and deploy programs: scan for threats, counter security measures, etc. Again, it’s actually quite intuitive, and if you don’t fancy it you can either skip the hacking missions or just vastly reduce the difficulty with perks and syringes full of hacking juice (referred to in-game by trained hackers as “hacking juice”). It’s not bad as a standalone palette cleanser and I appreciate a cyberpunk game actually attempting to dig into this stuff rather than just relegating it to a minigame. It also feeds into the fantasy nicely with how it folds back into the turn order, so your hacker can get caught or shot in realspace while they’re hacking, or you can designate a lookout while the rest of your team is off doing other things for some nice cinematic moments.

Right, review’s getting massive. Lots to cover, so here’s a quickfire round of spare bits I wanted to mention. Stealth is both encouraged and fun but so is violence, and there’s plenty of good abilities for going loud, too, like the gunslinger class you can arm with two revolvers then set to a unique overwatch where they go all cowboy Biff Tannen. The actual planning stage of the heists isn’t as deep as I’d hope for given the detail elsewhere, it’s really just a case of setting up fixer buffs, like temporarily disabling reinforcements or security cameras. Maybe choosing entry points or splitting your team up would break the mission design but it would suit the fantasy nicely. There’s also very little explanation of what stats actually do when you’re building your characters at the start (“too many decisions, too little context”, as Sin put it.)

But it does level out reasonably sharpish. And this isn’t me saying “it gets good after twelve thousand years”. It’s good from the beginning, it just takes a few hours to get a sense for the shoal of systems being spoon-catapulted at your face like soggy peas from a fussy toddler, or like water at my own face when I forget how spoons work. I’d hate for anyone to miss out because it seemed like obnoxious work to learn, basically, because the leather jacket’s a rental and the middle finger tats are temporary and it’s actually pretty easy going, just ambitious and detailed.

And I guess the last thing to mention is the game’s styling of itself as an RPG feels very much character sheet crunch and class led, not so much storytelling. Dialogue choices are about revealing worldbuilding or accepting missions. There’s a sense of your gang gradually building up a history and trajectory, if not your customised Cyber Knight as an individual. And it definitely pulls off the XCOM and Battle Brothers thing of making you very afraid when your favourite idiot has three overwatch cones trained on them.

This isn’t a criticism as much an attempt at elucidating what you’re getting here, and perhaps an acknowledgement that cyberpunk as a genre probably once held some aspirations to be a bit more insightful and incisive than whatever very fun but ultimately slightly goofy and perpetually unsurprising pastiche we end up with in many cases, even if you can hardly blame it for abandoning attempted prescience when we live in a state of ketamine-droopy tech mogul grins proudly announcing their investments in the The Torment Nexus v2.1.6. Making you feel cool probably isn’t the most important thing a cyberpunk game can do. Nonetheless, CK:F is pretty great at it.

Discover more from Webgames Play

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.